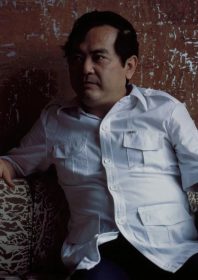

Date of birth: 29 April, 1932 (Beijing, China)

Date of death: 14 January, 1997 (aged 64), Taipei, Taiwan

Mandarin name: Hu Jinquan

Other names: Hu King-chuan, Wu Kam-Chuen, Frankie Gam Chuen, Hu King-Chuan, King Chuan, Hu Jing-Chuan, Chin Chuan

Occupation: Director, writer, editor, actor, set designer.

Biography: King Hu is one of China’s most respected and influential filmmakers, famous for historical martial arts films. Despite not being particularly interested in martial arts, he popularised the ‘new school’ wuxia (‘martial chivalry’) genre in the 1960s and helped to cultivate the role of the female knight-errant. King Hu was a scholar of Chinese history and a master filmmaker with wide-ranging cinematic expertise – he was an experienced actor who often directed, wrote, edited, designed and funded his own films. Despite his cross-cultural appeal – he was the recipient of the ‘Technical Grand Prize’ at the 1975 Cannes Film Festival and his work has been lauded by filmmakers ranging from Tsui Hark to Ang Lee to Quentin Tarantino – many of his latter-day films did not perform well domestically upon released. However, his themes of Chinese history and Buddhist philosophy, plus his impressive visual style and strong female characters, have seen his films become more important retrospectively.

King Hu (Mandarin name: Hu Jinquan) was born and educated in Beijing. He was the only son to an artist mother and mining engineer father. Hu read a lot as a child and travelled extensively in northern China. He was educated at Huiwen Middle School and the Peking National Art College. Hu was fascinated by the Beijing Opera as a child, an influence which would become a major facet of his film work – although he did not show much interest in working in films until his relocation to Hong Kong in 1949, soon after the Chinese Communist Revolution which saw the formation of the People’s Republic of China and the remnants of the Nationalist government retreating to Taiwan.

Following the revolution, Hu was seemingly left trapped in Hong Kong – a British colony. He initially found work as a journalist, tutor and artist, and drifted into the film business when his talents in calligraphy and set design saw him work on Mandarin films in the 1950s. He also became recognised as an actor after being spotted by veteran director, Yan Jun, who, in 1954, cast him in Humiliation for Sale. Given his short, tubby look, King Hu became a popular character actor and something of an audience favourite. He also found work in radio as a broadcaster, and worked as a producer for Voice of America in Hong Kong. (King Hu was well known at the time for his fascination with America, and was said to have owned Hong Kong’s first open-top Cadillac.)

Hu became friends with the director Richard Li Han-hsiang, who had worked as Yan Jun’s assistant. When businessman Run Run Shaw arrived in Hong Kong from Singapore to set up his own production company, Shaw Brothers, Richard Li was one of the first directors under contract, eventually becoming the fledgling studios’ premier director (Li’s 1962 film, The Magnificent Concubine, would become the first Chinese-language film to win a prize at Cannes). Li also convinced King Hu to join the studio and, in 1958, he signed a contract with Shaw Brothers as an actor and scriptwriter.

While under contract at Shaw Brothers, Hu scripted films like The Bride Napping (1962) as well as working as an actor. He started to make the move into directing – firstly as an assistant to Richard Li on films including The Love Eterne (1963), a hugely successful musical romance based on the much-told story of the ‘butterfly lovers’. Because of pressures to complete the film due to a rival company producing a version of the same story, Li handed the writing and directing of sections of the film to King. In 1964, still overseen by Li, King Hu directed The Story of Sue San, an historical Chinese opera based on a 17th century story by Ming dynasty writer, Feng Menlong. (Because of his fascination with the period, many of King Hu’s later productions would also be set during the Ming dynasty).

Despite still being contracted as a writer and actor, in 1964, King Hu directed his first solo project, Sons of the Good Earth, a rare ‘contemporary’ film in his filmography, set during the second Sino-Japanese war. Hu also wrote and acted in the film, drawing praise for his patriotic portrayal of a guerrilla leader, Hu’s only heroic role as an actor.

His next film, Come Drink With Me (1966), was a surprise success and would establish him as a director of wuxia pictures. Based on The Drunkard Beggar, a 1920s Chinese operathat King Hu loved as a child written by novelist Huanzhu Louzhu and set during the Ming dynasty, Come Drink With Me reworked the conventional wuxia martial arts film by depicting violence realistically – even if it does still contain aspects of fantasy and special effects prevalent in the ‘old school’ wuxia films of the time – and established the female knight-errant as the genre’s archetypal protagonist (named ‘Golden Swallow’, she is played by the 19-year-old actor, Cheng Pei-pei).

The huge success of Come Drink With Me – and King Hu’s next film, Dragon Inn – firmly established the ‘new school’ wuxia film as the dominant genre in Hong Kong action cinema, and sparked a slew of copycat productions, many of which borrowed the film’s inn setting and its swashbuckling female hero.

Unhappy at Shaw Brothers due to the lack of creative control afforded to filmmakers, King Hu planned his exodus from the studio by negotiating a deal with Taiwan’s Union Film Company. His mentor, Richard Li, had made a similar move in 1963, when he set up The Grand Motion Picture Company with Union and the Singapore-based Cathay Organisation, although the venture had ended in financial disaster in 1966. Originally founded as a distribution company in 1953, Union hired King Hu as its production chief when the company made the decision to produce its own films. Hu was responsible for training new talent and buying equipment to facilitate its studio operations, and the production studio was established off the back of Hu’s next film, Dragon Inn (1967).

Hu had originally wanted to make a film based on the short story, The Painted Skin – written by Pu Songling (1640-1715) from the Liaozhi anthology (‘Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio’) – but the story had fallen foul of the strict censorship system in Taiwan installed by the Nationalist government. (Hu did eventually make The Painted Skin into a film, which would turn out to be his final film). Instead, Hu’s Dragon Inn saw the director return to the wuxia genre.

With its Ming dynasty setting based around an inn besieged by various figures from the jianghu (‘martial world’), including a new female knight-errant star in 17-year-old Polly Shang Kwan, Dragon Inn established the Union house style for martial arts pictures and launched the wuxia genre in Taiwan. It was also the most successful Chinese film in history at the time, earning over HK$2m in Hong Kong alone, famously out-grossing The Sound of Music. (Not that Union saw many of the profits, having sacrificed the film’s overseas rights to Shaw Brothers to settle King Hu’s contract dispute with the company).

The film is also notable for supposedly being the first to include a credit for ‘martial arts director’, evidently underlining how important King Hu considered the role. The inaugural credit went to Beijing Opera-trained Han Ying-chieh, who had also worked on Come Drink With Me and helped to establish King’s percussive, trampoline-assisted, dance-like action sequences. The film’s non-conventional narrative structure also evoked the ‘new wave’ directors of the time, like Jean-Luc Godard, again making Hu’s approach feel fresh and modern.

Buoyed by the success of Dragon Inn, Hu’s next picture would prove to be his masterpiece, A Touch Of Zen (1971). The film is an adaptation of another Pu Songling short story from the Liaozhi anthology, Xianü (‘Heroic Woman’), and is King Hu’s ode to the knight-errant, with themes of martial chivalry, female empowerment and Zen enlightenment, told through a mixture of genres: wuxia, espionage, and fantasy. The film’s titular ‘heroic woman’ was played by Hsu Feng, who had appeared in a small role in Dragon Inn, and following her excellent turn in A Touch of Zen, she would become one of King Hu’s go-to lead actors.

It was Hu’s most ambitious film and was released in two parts in Taiwan – the first in 1970, and the second in 1971. Neither version performed well domestically, and in Hong Kong, where the film was cut down and released in a single two-and-a-half-hour version, it also flopped. The success of Bruce Lee’s The Big Boss extinguished the popularity of the ‘new school’ wuxia film and ushered in a new era of kung fu films. It also caused the end of Union as a production house. After failing to recoup a lot of the money it had invested into A Touch of Zen, the company moved into kung fu movies – including work with Jimmy Wang Yu – but struggled to compete and eventually ceased production of films in 1974.

While in Taiwan, King Hu contributed a short, 40-minute film as part of a portmanteau project called Four Moods (1970), designed as a vehicle to kickstart his old mentor Richard Li’s new production company, New Grand. Hu’s contribution, ‘Anger’, is considered to be one of his masterpieces, and forms part of his ‘inn cycle’ – it is based on a famous Beijing Opera story, San Cha Kou (‘At The Crossroads’), set inside a tavern where characters reside with conflicting motives.

The failure of A Touch of Zen was a major setback for King Hu. He returned to acting, appearing in The Yin and the Yang of Mr. Go (1970), directed by and starring Burgess Meredith – alongside James Mason and a young Jeff Bridges – which was being shot in Hong Kong. He eventually left Taiwan for Hong Kong in 1971 when he signed a contract with Raymond Chow at Golden Harvest. In a similar deal to Bruce Lee’s and the creation of Concord Production – partnering with Golden Harvest – King Hu followed suit to create King Hu Film Productions with Raymond Chow as a partner.

Two films were made. Both films reflect a break away from the ‘new school’ wuxia tradition that King Hu helped to develop and popularise, featuring more kung fu-inspired action with assistance from Golden Harvest’s in-house action director, Sammo Hung. The first film, The Fate of Lee Khan (1973), concludes King Hu’s ‘inn cycle’ and focuses on the establishment of the Ming state during the final days of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The film featured many variants of the female knight-errant character, all fighting for a nationalist cause. Hsu Feng played a villain in the film, and there were roles for Polly Shang Kwan, Angela Mao Ying, Helen Ma and Hu Chin.

Hu’s second film with Golden Harvest, The Valiant Ones (1975), again featured unarmed combat courtesy of Sammo Hung, and bit parts for his fellow Beijing Opera-trained stunt performers, including Jackie Chan, Yuen Biao, Yuen Wah and Corey Yuen. Hu also found a role for Hsu Feng, playing the only female warrior in the film. Considered to be the last of his wuxia pictures, neither The Fate of Lee Khan nor The Valiant Ones performed well at the box office. However, his fortunes turned around when A Touch of Zen was awarded the ‘Grand Prize for Superior Technique’ at the 1975 Cannes Film Festival. The prize recognised his talents as a cinematic auteur and helped to raise the international profile of Chinese cinema.

In 1977, Hu married the writer and scholar, Chung Ling. She received her Doctorate in Comparative Literature from the University of Wisconsin, and wrote several books on Chinese literature, including Orchid Boat: Women Poets of China, in 1972. (The couple would later divorce in 1991). Also in 1977, Hu published his own literary study on the famous Beijing writer, Lao She, entitled Lao She and His Works. When the couple married, Chung Ling resigned from her teaching post at the State University of New York at Albany to become the financial controller and advisor to Hu’s company, King Hu Film Productions.

Thanks to connections she had made in South Korea – one of the few places in which there are relatively untouched Ming dynasty temples and period-appropriate locations outside of mainland China – the two set about writing scripts for his next project. Due to the need to appease its tightly controlled film industry, and unlock vitally important financial incentives, there was an imperative on foreign filmmakers to make more than one film during their time in Korea. King Hu wrote what would become Raining in the Mountain, a wuxia-adjacent story focusing on the contradictions within Buddhism; and Chung Ling wrote Legend of the Mountain, an epic ghost story set during the Sung dynasty – the first time Hu would direct a film not based on one of his own scripts. Both films were shot back-to-back – and often simultaneously – over the course of a year from 1977 to 1978, with much of the same cast and crew appearing in both films, including Hsu Feng, Shih Chun, and the fight choreographer and actor, Ng Ming-tsui.

When Raining in the Mountain premiered at the Hong Kong Film Festival in 1979, it failed to pick up many foreign sales, and neither Raining or Legend performed well. Legend of the Mountain was reduced from a three hour film to under two hours, but again it did not perform well. Tastes had moved on, and King Hu had failed to move with the times. At the start of the 1980s, he based himself in Taiwan, where he made a social satire set in modern Taiwan, The Juvenizer (1981). It was designed as a benefit to help lift King Hu out of financial trouble, and starred many great actors of the time. In 1983, he released two more films – All the King’s Men, a historical court drama with roles for King Hu regulars like Tien Feng and Cheng Pei-pei; and The Wheel of Life, a Taiwanese anthology film which saw him reunite with his Four Moods co-directors Li Hsing and Pai Ching-jui.

In 1984, King Hu moved to California, where he would spend much of his final years trying to make his first English-language project, I Go, Oh No (aka The Battle of Ono), about the Chinese immigrants who built the railroads in California in the 19th century. However, unlike Akira Kurosawa – who had fans in the west like Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas who could help him to finance films – King Hu was a lesser-known figure in Hollywood and he struggled to get the project off the ground.

Meanwhile, in Hong Kong, the wuxia genre was being rejuvenated again for modern audiences thanks to many of the ‘new wave’ directors who were heavily influenced by King Hu’s work – people like Tony Ching Siu-tung, Wong Kar-wai, and especially Tsui Hark, who would produce his own remake of Dragon Inn, called New Dragon Gate Inn, in 1992. In 1990, King Hu would work with Tsui’s production company, Film Workshop, on The Swordsman. Based on The Smiling, Proud Wanderer – a novel by one of the most famous ‘new school’ wuxia authors, Louis Cha (aka Jin Yong) – King Hu would ultimately leave the production before completion after disagreements with Tsui, resulting in a number of directors (including Tsui) finishing the film.

Hu’s final film, Painted Skin (1993), finally saw him realise his ambition to bring Pu Songling’s short story to the screen. It also finally saw him shoot in his home of mainland China. The Hong Kong supernatural film was produced by Ng Ming-tsui – collaborator on his Mountain films – and features an all-star cast including Adam Cheng, Joey Wong, Sammo Hung, Wu Ma, and Lam Ching-ying.

Based in Pasadena, he had planned to return to Southern California to start filming on The Battle of Ono when he briefly flew back to Taiwan to attend the memorial service of his mentor, Richard Li Han-hsiang, who had died of a heart attack in Beijing on 17 December 1996. While in Taipei, he underwent a checkup due to chest tightness, and was recommended an angioplasty to widen his coronary arteries (he had already had two successful procedures previously done at the same hospital in 1986 and 1993). However, due to complications arising from the surgery, King Hu died on 14 January 1997, aged 64. He was cremated in Taipei on 31 January 1997, and his ashes brought back to the USA, where he was laid to rest at the Rose Hills Memorial Park in Whittier, California.

Over his lifetime, King Hu won many awards. He garnered Best Director and the Lifetime Achievement Award at Taiwan’s Golden Horse Awards in 1979 and 1997, respectively. In 1991, Hu was honoured at the Los Angeles Film Festival, sponsored by the American Film Institute. In 1992, King Hu was honoured with a Lifetime Achievement Award by the Hong Kong Film Directors’ Guild.

His legacy as a pioneer of wuxia cinema has been profound, and his influence can still be felt today, especially in the figure of the female knight-errant which he helped to popularise – such characters can be found in the work of Ang Lee (Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon), Zhang Yimou (House of Flying Daggers), and Hou Hsiao-hsien (The Assassin). The King Hu Foundation, set up in Pasadena by Cheng Pei-pei, is dedicated to preserving the legacy of the filmmaker through screenings and promotional activity. Many of his films have been lovingly restored by the Taiwan Film Institute and are available on Blu-ray and DVD formats around the world.

Speech! “One of the main differences between my films and most other Hong Kong films with period settings [is that] others approach the past for its exoticism, but I try to approach the past with respect. As you know I have a special interest in the Ming dynasty, and I try to give careful attention to the accuracy of set and costume details, but also, more significantly, to the manners and mores of the period. I don’t think you’ll find any psychological anachronisms in my film.” Quoted in the programme notes for the 23rd London Film Festival in 1979, where Raining in the Mountain was shown.

Filmography (as director*): 1964 The Story of Sue San (+ scr.); 1965 Sons of Good Earth (+ scr, cast); 1966 Come Drink with Me (+ scr.); 1967 Dragon Inn (+ scr.); 1970 Four Moods (+ scr.); 1971 A Touch of Zen (+ scr.); 1973 The Fate of Lee Khan (+ scr.); 1975 The Valiant Ones (+ pro, scr.); 1979 Raining in the Mountain (+ scr.); Legend of the Mountain; 1981 The Juvenizer (+ scr.); 1983 All the King’s Men (+ scr.); The Wheel of Life; 1990 The Swordsman; 1993 Painted Skin (+ scr.).

Filmography (as actor*): 1956 Red Bloom in the Snow; Golden Phoenix; The Long Lane; 1957 Cha Cha Girl; Lady in Distress; Sisters Three; Springtime in Paradise; Little Angels of the Streets; The Frosty Night; Riots at the Studio; Love Fiesta; 1958 How to Marry a Millionaire; The Shoeshine Boy; Laughter and Tears; Little Darling; The Angel; The Blessed Family; The Magic Touch; 1959 Dear Girl, I Love You; The Kingdom and the Beauty; 1960 The Deformed; Rear Entrance; How to Marry a Millionaire; When the Peach Blossoms Bloom; 1961 Les Belles; The Swallow; Kiss for Sale; The Girl Next Door; The Fair Sex; The Pistol; 1962 Dream of the Red Chamber; 1963 Love Parade; Three Dolls of Hong Kong; Revenge of a Swordswoman; My Lucky Star; The Empress Wu Tse-tien; 1964 Between Tears and Laughter; The Dancing Millionairess; 1970 The Yin and Yang of Mr. Go; 1971 Money and I.

Filmography (as writer*): 1962 The Bride Napping; 1966 Downhill They Ride; 1973 Heroes of the Underground; 1975 Dragon Gate.

Sources: Filmography from HKMDB.com; article from UK annual International Film Guide 1978, Sino-Cinema; King Hu on Encyclopedia.com; Los Angeles Times obituary; Tony Rayns audio commentary – Raining in the Mountain (Eureka Entertainment), Legend of the Mountain (Eureka Entertainment); David Cairns video essay – Raining in the Mountain (Eureka Entertainment), Legend of the Mountain (Eureka Entertainment); Stephen Teo – ‘Chinese Martial Arts Cinema: The Wuxia Tradition’; Avenue of Stars website, Hong Kong; ‘Cannes’ Affection for Films from China’, china.org; King Hu on Wikipedia; ‘The man who journeyed to the heart of Peking Opera’, China Daily; Introduction to ‘Lao She and His Works’ by King Hu; The Wheel of Life, programme notes from Far East Film Festival 2019; King Hu Foundation on Instagram; image from Taiwan Panorama.