Taiwanese auteur Hou Hsiao-hsien’s first film in eight years is also his first attempt at a wuxia genre piece. But this is a massive running leap away from more commercial wuxia offerings like Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, or even most of King Hu‘s seminal work. The King Hu comparison is an apt one, considering how this film was decorated with art-house awards at the 2015 Cannes Film Festival, much like Hu’s A Touch of Zen in 1975. Hou pays lip service to classical jianghu traditions – a flying female knight-errant, a strange supernatural subplot, a wandering kung fu nun on a misty mountaintop – but these are essentially peripheral concerns. Hou is more interested in the everyday – the mundane, even. His lens lingers for extended, hypnotic lengths of time on seemingly innocuous moments: a child catching a butterfly; a bird at twilight cutting through a winter landscape; a farm of goats resting and feeding. The soundtrack follows suit: sparse single beat drumming over birdsong and the contemplative sounds of nature. The overall effect is beguiling, and perhaps the most seductively accurate portrayal of life in ninth century China that has ever been captured. Every frame is exquisite and littered with astounding detail (Hou researched the period fastidiously for many years before making the film, from the literature of the time to the type of fabrics worn, and it clearly shows). Hou isn’t even particularly restrained by story, although the film is supposedly based on a wuxia text. Instead, we dive into debates at an imperial court with little or no context, and some characters – like a bearded mystic – appear without any explanation.

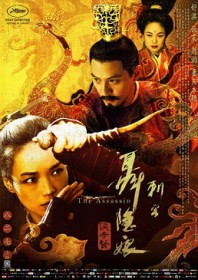

The film stars two of Hou’s favourite actors, Shu Qi and Chang Chen. Shu plays Nie Yinniang, kidnapped at the age of 10 by a kung fu nun and trained to become a lethal assassin. She fails to kill a government official when she discovers him at home cradling his infant son. As punishment, the nun sends her back to Weibo province in northern China to enact one final hit: to kill her cousin, the prominent governor Tian Ji’an (Chang Chen), of whom she was once betrothed. It is never quite clear as to any of the character’s motives, and those looking for a more concise, atypical narrative may find the deliberately opaque set-up frustrating. Those looking for the heart-racing fight sequences of Crouching Tiger will also be disappointed, because although the film contains some sublime action, this is far from an action movie. The combat scenes are quick, efficient, and performed very much in the style of a Japanese chanbara, adopted by Hou in a bid to spare his actors from the exhausting strain of having to perform long fight sequences. One fight scene takes place on the edge of the frame, obscured by a woodland scene, placing the viewer in a voyeuristic position. It is a position we retain throughout the film, whether we are observing Tian Ji’an and his concubine from behind the room’s slowly moving drapes, like his eagle-eyed assassin, or whether we take a birds’ eye view from atop the snowy peaks of a mountain as a cloud disperses to obscure the view. This scene, in particular, is the moment when the film starts to resemble something transcendent. Films like this are a very rare and beautiful thing.

- Country: China, Hong Kong, Taiwan

- Directed by: Hou Hsiao-hsien

- Starring: Chang Chen, Satoshi Tsumabuki, Shu Qi, Zhou Yun

- Produced by: Huang Wen-ying, Liao Ching-sung

- Written by: Chu Tien-wen, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Hsieh Hai-meng, Zhong Acheng

- Studio: Central Motion Pictures Corporation, China Dream Film Culture Industry, Media Asia Film Company, Sil-Metropole Organisation, SpotFilms, Zhejiang Huace Film & TV