Zhang Yimou’s return to the wuxia film is also a massive return to form; a delicate, deceptive and deadly tale of warring states which seemed to sneak onto streaming services without much fanfare, in stark contrast to the reception received for the co-produced Chinese-American flop, The Great Wall, which featured Matt Damon fighting a swarm of giant lizards. There is not a single CGI monster in sight in this film – thank god – but there is plenty of what fans of Zhang Yimou’s breakout wuxia successes like Hero and House of Flying Daggers will find more familiar; plotting and subterfuge, romance and revenge, and sumptuous, exquisite cinematography.

The ‘shadow’ in the title acts as a through-line to connect so much of this wonderfully enveloping film, not just narratively speaking, but also visually and physically. A crippled commander in the Pei Kingdom orchestrates an audacious bid for power and revenge from within the hidden walls of the palace. Since his defeat at the hands of a rival general, the commander has holed himself up in secret to train his loyal servant, Jing, to assume his identity and take his revenge. Both Jing and the spectral, ghost-like commander are played by the same actor, Deng Chao, in a remarkable dual role. Jing is the commander’s ‘shadow’, fooling his unpredictable young ruler (Zheng Kai), who inherited the Pei Kingdom following the death of his father and whose readiness to acquiesce in the name of peace with rival states is seen as an affront to the proud reputation of his people. The only person aware of the ruse is the commander’s wife (Sun Li), who must pretend that Jing is her real-life hubby, inevitably leading to a ménage à trois reminiscent of the central love triangle in Hero.

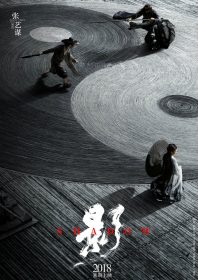

A more physical interpretation of the ‘shadow’ trope is represented through the teachings of tai chi, and its emphasis on the balance of elemental forces. Over a giant yin and yang symbol – itself a shadow-like mirror image (the film’s Chinese title is Yang) – Jing discovers that the only way to combat the ferocious, heavy attacks of his rival, General Yang (Hu Jun, a class act), is to adopt a more ‘feminine’ style of combat; essentially pitting fire against water to redress the balance in the fight. A third, more ethereal interpretation of ‘shadow’ can be found in the spellbinding work of Zhang’s Academy Award-nominated cinematographer, Zhao Xiaoding, who fills the film’s monochrome palette with the most extraordinary balance of light and shade. It’s not quite a fully black and white film, but at times it looks a lot like one, with only flashes of colour punctuating through the greys: skin tones, white robes, red blood. It’s a vivid, clever, intoxicating visual approach which, when coupled with the film’s exotic use of diegetic and non-diegetic sound (mostly indigenous instrumentation from the period, including zithers and flutes, plus the incessant, foreboding sound of rainfall), makes the film feel like an assault on all of the senses.

And this is all unfolding before the film really kicks into action, when the Pei Kingdom make their attempt to invade the walled Jing City. An androgynous army wielding revolving, bladed umbrellas are smuggled in via a giant floating bamboo stage to take on the Yan army. It is at this point when you realise that for all of Zhang Yimou’s extraordinary storytelling talent, idealism and sensual vision, he is still not beyond the temptation to include a scene in which an army, shielded inside spinning downturned umbrellas, slide across a rain-drenched street throwing knives at their enemies like a lethal swarm of vicious clams. And, for that, we can only love him even more. Bravo.

- Country: China

- Action Director: Feng Weilun, Lin Zhitai, Tang Tengfei

- Directed by: Zhang Yimou

- Starring: Deng Chao, Guan Xiaotong, Hu Jun, Sun Li, Zheng Kai

- Produced by: Liu Jun, Wang Xiaozhu

- Written by: Li Wei, Zhang Yimou

- Studio: Bodi Media Company, Bona Film Group, Culture Media, LeVision Pictures, Perfect Village Entertainment, Shanghai Tencent Pictures, Tencent Pictures, Tianjin Maoyan Weying Media