In 2003, Leon Hunt published Kung Fu Cult Masters: From Bruce Lee to Crouching Tiger, his definitive study on a much maligned film genre. Over a decade later and the ‘cult’ surrounding the kung fu film has infiltrated the multiplex. The digital age has created unlikely action heroes from animated pandas to mainstream superheroes. So what’s next for the kung fu film? We chat to the film scholar ahead of his BFI lecture on the transnational success of the Chinese martial arts film.

As part of their A Century of Chinese Cinema season, the British Film Institute (BFI) has prepared a special tribute to one of China’s most popular, prolific and profitable exports: the kung fu film. The choice of classic films put forward by the BFI covers a neat chronological cross-section of the genre, detailing its evolution from the 1940s with a rare screening of the very first black and white Wong Fei-hung film starring Kwan Tak-hing (these films are regarded as the first real kung fu films in terms of stylistic focus and choreography). The list then travels from Shaw Brothers swashbucklers to the rise of Bruce Lee, Jackie Chan and the ‘new wave’ action of the 1980s, to Jet Li and the ‘martial arthouse’ films of Zhang Yimou and Ang Lee.

This is the story film lecturer Leon Hunt wrote about in studious detail for his 2003 book Kung Fu Cult Masters, one of the most comprehensive studies on the genre so far. He will be giving a special illustrated lecture as part of the BFI season discussing the transnational evolution of Chinese martial arts cinema, charting the genre’s global significance and influence on some of the world’s greatest filmmakers.

This is the story film lecturer Leon Hunt wrote about in studious detail for his 2003 book Kung Fu Cult Masters, one of the most comprehensive studies on the genre so far. He will be giving a special illustrated lecture as part of the BFI season discussing the transnational evolution of Chinese martial arts cinema, charting the genre’s global significance and influence on some of the world’s greatest filmmakers.

But a lot has happened since the book’s release. Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) – an Oscar-winning tribute to the wuxia films of Lee’s childhood – sparked a rise in China of the so-called martial arthouse films: sprawling, exotic, high concept swordplay in period costume and filmed on an epic scale. Hong Kong, meanwhile, focused more on the promotion of pop singers than kung fu stars, and as the likes of Jackie Chan, Sammo Hung and Jet Li enter their old age, there is no younger generation of performers ready to take their place. The best kung fu films of the last 10 years have not even been made in China. Ong-Bak (2003) was a Thai production and Gareth Evans’ The Raid films are of Indonesian origin, although their intensely physical, intricately choreographed fight scenes owe a huge debt to the Hong Kong kung fu films of the 1970s and 80s.

“I think for quite some time now, Hong Kong cinema has had less of an investment in the idea of the authentic than a lot of its western fans have,” says Leon. “I think there came a point where that idea of the real and the authentic just started to seem old fashioned.” The void, he says, has been filled by filmmakers in other parts of the world who have grown up watching Hong Kong action films – people like Tony Jaa and Gareth Evans. “What they do in both cases is indigenise the action by simply applying it to the local martial art.

Iko Uwais and Cecep Arif Rahman exchange silat skills in The Raid 2 (2014). Image: The Guardian

“I think the impact of Ong-Bak was maybe a bit of a wake up call, or a reminder to some Hong Kong filmmakers that they used to be able to do that kind of stuff too,” he says. “Also for some time now the Hong Kong star system has been organised much more around pop music than a capacity for physical action. That doesn’t put a sell-by date on the genre because there are always ways of making other people look impressive – you can double them, or use CGI. But it certainly puts a sell-by date on a certain type of Hong Kong martial arts star, because once Jackie Chan and Jet Li and Donnie Yen have gone, there just aren’t any more.”

But even if Hong Kong no longer raises the bar in terms of physical action, it is still constantly evolving and reinventing itself. This even applies to its home grown talent. Leon is particularly encouraged by the recent emergence of Donnie Yen as a genuinely bankable leading man, an honour which seemed to have alluded him his whole career until films like SPL (2005), Flash Point (2007), and Ip Man (2008). “[But] it is very telling that when Hong Kong cinema was looking for somebody with leading man status to be able to do that kind of gritty physical action, they turned to a man in his 50s,” Leon says.

“I don’t agree with those fans who want us all to go back to the 1970s and shoot it like a Shaw Brothers film, but neither do I think it needs to be all about the digital now.” Leon believes technological advances in action cinema has been both a help and a hindrance to the kung fu film. Following the huge impact of The Matrix in 1999, Hong Kong inevitably followed Hollywood down the digital path. He cites Tsui Hark’s Detective Dee and the Mystery of the Phantom Flame (2010) as an example of CGI done well, but Jet Li’s Badges of Fury (2013) highlights perfectly how the genre can get it wrong. “I don’t have a problem with this because it’s fake. I have a problem with this because it’s just not very interesting to look at,” he says.

Leon lectures at London’s Brunel University teaching modules on many subjects including Hong Kong cinema and Jet Li as a transnational star. For his Hong Kong module, he shows his students a kung fu film and a wuxia film. For his Jet Li pupils, he currently uses the film Fearless (2006) as his case study. He says as well as displaying the light and dark aspects of Jet Li’s onscreen persona – something Hollywood has never fully understood – the film also explores the fragility of Chinese kung fu in the wake of modern technological warfare. “Fearless suggests that Chinese martial arts will take on a symbolic function. It will no longer be about fighting people as it will be useless in warfare, so you use it to cultivate the spirit and celebrate the best of Chinese culture.”

Indeed, many of the films being shown by the BFI over the next few months serve a similar purpose. For legions of fans around the world, kung fu films represent a cross-cultural window into a unique, foreign and exciting world. Leon, as an English boy growing up in the 1970s, knows only too well the captivating and hypnotic power of these films ever since he first saw Bruce Lee on the big screen. Crucially, he is very self-aware on how his own perspective has impacted on his ongoing commentary regarding Chinese martial arts films. “I was aware inevitably [when researching the book] that there were areas where I was going to have blind spots,” he says. “I can’t pretend to grasp every single cultural nuance. As much as I tried to research things and get things right, there were certain things I’m sure a Chinese critic sees automatically that is likely to pass me by.” Some of his most pleasing feedback for the book has come from Chinese commentators. As further validation of his research, the book has now been published in a Chinese language edition.

The book focuses on a number of topics from the dominant female characters in wuxia cinema to the homoeroticism at the core of particularly Chang Cheh’s male-dominated ensembles, not to mention narrative dissections on genre tropes like the often used master-pupil device. But it was the chapter on the Shaolin temple which caused Leon the biggest challenge. “I kept finding more and more films and getting more fascinated in the different versions of the different legends,” he says.

His book shines an intellectual light on a genre which is much maligned by film academics. Why does he think this is the case? “I think often a distinction gets made between story and action, and somehow action is a poor substitute for story,” he says. “Then, when the martial arthouse films came along, there was the perception that, ‘oh, now they’ve got good stories as well, and they’ve got proper directors making them’. But action often tells a story. Many of these fight scenes tell stories in themselves, and they’re exploring ideas around martial arts styles and learning processes.”

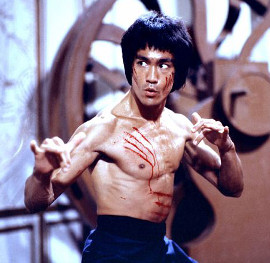

The turning point was, of course, Bruce Lee. It is hard to overstate the impact of Bruce Lee in the 1970s, says Leon, who is still intrigued by the world’s first martial arts movie star. “There is something about him that remains incredibly modern,” he says. “Up to Bruce Lee, being an actor in martial arts films did not really require you to be a martial artist, any more than being in a western required you to be a brilliant shot with a gun. You just needed to look good with a sword. Bruce Lee comes along and he’s in another league, he’s on another level.

“There is a turning point in Fist of Fury when he fights Bob Baker, the Russian fighter at the end. That’s the first fight when you’re seeing the fully formed Bruce Lee style. It’s a very grounded fight. There’s no trickery. You’re seeing his real speed and you’re seeing a kind of psychology to the fight. The fight tells a story. He psychologically breaks him as well as beating him physically.”

In discussing Bruce Lee for the book, Leon took an alternative approach by studying the pseudo-Lee films of Bruce Li and the many other imitators that emerged after Lee’s death. These ‘clone’ films may be rightly labeled as a tacky and exploitative by-product, but Leon says they stand for something far more interesting. “They’re trying to make sense of Bruce Lee in some way [and] what he meant,” he says. “He’s a hugely contested figure both among fans of the genre and in scholarly accounts. I have read critical accounts that say he’s a Chinese hero and that westerners don’t really understand him, which I think would have come as news to Bruce Lee himself. There are others who approach him as a much more global, westernised figure. I guess that’s part of the conundrum of Bruce Lee, really, because he’s positioned in both industries and he died at the point he was working in both of those industries at the same time.”

Over a decade on and Leon clearly still has a keen passion for the genre. He has written other books – most recently about The League of Gentleman TV show for the BFI in 2008 – but is he ever likely to return to the kung fu genre? “It’s always going to be a passion of mine,” he says. “I still love the genre and there are still martial arts films coming out that I enjoy. Finding an angle where it would make another book; that might take some time. But I don’t rule it out.”

Image sources: Enter the Dragon from Daily Mail; Kung Fu Cult Masters book cover from Amazon