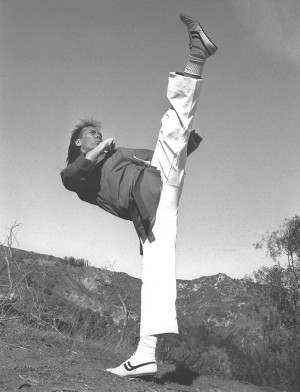

Stuntman, fight choreographer and author John Kreng has worked in the Hollywood film industry for nearly three decades.

Despite starting his career as a stand up comedian, John Kreng has worked with many legends of action cinema, including Jet Li, Tsui Hark, David Carradine and Yuen Cheung-yan.

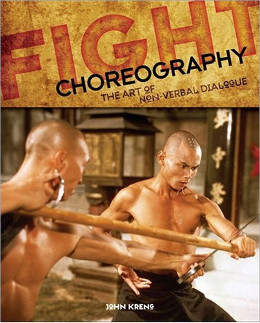

Kreng is the author of Fight Choreography: The Art of Non Verbal Dialogue and has written extensively about the history and methods used in martial arts movie-making, as well as teaching seminars on how to fight on film. In 2013, Kreng was inducted into the Martial Arts History Museum’s Hall of Honor. He is working on a follow up book, The Fight Choreographer’s Hand Book, tentatively scheduled for release in 2014.

KFMG: Movie stars often boast about performing their own stunts. How true is this?

JK: Some actors are able to do their own stunts and others can’t, or simply don’t. A lot of this has to do with insurance issues. If a principal actor gets hurt, the whole production schedule grinds to a halt, which can mean a loss of millions of dollars, and many jobs are lost too. Some actors go on talk shows and say they do all their own stunts – even though they might not – because they feel it ruins the magic of what they do. But others like Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger are more open about it and freely admit when they were doubled.

What traits are consistent with all the best screen fighters?

Stage presence and charisma is the first thing. It’s hard to explain, but it’s an aura and presence they display when the camera is focused on them. You can’t see it, but it’s something you definitely feel. There is a sense of confidence that exudes from them when they fight for the camera. When you’re fighting them, you also have to be able to hold your own and be able to know when to yield and flow with them. When you go through this with seasoned professionals, it is truly a magical process to be a part of.

John Kreng (left) tussles with Jet Li in The Master (1989)

With every new project, what process do you go through to find the right style for the characters?

A great fight scene has to be supported by a great story and character motivations that justify any type of action, be it a car chase, explosion or a fight. Otherwise it doesn’t matter and the audience will immediately forget about what they saw right after their butts leave the seats, and all that hard work in arranging and performing the action just went down the drain.

When it comes to choreographing fights, the script usually reads something like, “and they fight!” So essentially what we have to do is extrapolate and do detective work with what we know so far from what we read in the script, and interpret what we feel is appropriate to serve the story and the characters. Also, further down the process, the abilities and interpretation from the actors, the needs of the director and producer, the budget, the time given to train, rehearse, and shoot the action, along with how the fights are shot and edited have a huge influence on the final product.

Can you think of examples where filmmakers have got the fight scenes wrong for the type of film and its characters?

A common mistake I see is associating visual aesthetics with box office receipts. The Musketeer (2001), for example, was heavily influenced by the impact of The Matrix (1999). It soon became a popularity contest where every action film had to use wires and Hong Kong style fight choreography. The problem was the Hong Kong style of fighting looked out of place for the time period. However, the TV show Xena: Warrior Princess (1995-2001) was able to get away with it because it was a fantasy based on a mythological time and place, so the audience was less discerning.

Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story (1993) used the Jackie Chan avoidance/acrobatic style of fighting for the movie because they felt Bruce Lee’s approach to fighting on film was too boring in comparison. On the surface, I can understand and see that. What the filmmakers did not look into and research was Jackie’s style of fighting was created as the antithesis of what Bruce would have done on film. As a result, the fights really did not match Bruce’s personality. This is why it is important for filmmakers (and especially fight choreographers) to know and understand film history as well as the evolution, origins, and various approaches to action and fight choreography in film.

Then there’s the jittery handheld camera and getting the camera angles extremely tight so that you can’t see what is going on. It used to be that you only did that when an actor could not perform the moves and you needed to see their face in the shot. What they are doing is robbing the audience of the visceral experience of witnessing the cinematic moment happening right before their eyes. Some consider this a style because it’s now a common thing. However, I don’t. To me, they are either being lazy and/or they are simply showing they do not want to take the time or have any idea on how to craft the scene. The newer generations of filmmakers rave about The Raid (2011) because you could actually see what they were doing. What a novel concept!

So how much power does the fight choreographer have during the editing process?

So how much power does the fight choreographer have during the editing process?

Choreographers who can’t go in to help edit are at the mercy of the editor’s choices. I feel they should have the fight choreographer in the editing room to show them what they choreographed and how the segments are supposed to be pieced together. I was lucky enough to go into the editing room for Battle B-Boy (2014) for all 24 fight sequences, but it is rare. If a choreographer doesn’t know at least their camera angles and edit points, they need to learn ASAP.

There needs to be more seasoned stunt professionals going to film schools and teaching filmmakers what they need to know to improve their thinking and understanding of what it is we do as stunt professionals. Because what we do is so physically demanding, the generalisation is that stunt professionals are just a bunch of dumb jocks who do crazy things for the camera and don’t understand the technical aspects of making a movie. That is very far from the truth. What we do is an art and a science.

It took Hollywood a long time to catch up with the high standard of fight choreography happening in Asia. In your opinion, how healthy is the fight industry in Hollywood at the moment?

I feel the art of fight choreography is severely under appreciated in Hollywood. I have some friends who have been in the business for over 20 years as fight choreographers on some very high profile films and they can name only two or three things they have done they are truly proud of once the film was edited and released. In the west, action films give less time to shooting the action than they do with shooting the dialogue. When Steve Wang shot Drive (1997), he had two full crews working 12 hour shifts each in order to make the 30 day deadline.

In Asia, the emotions in a fight are extremely varied and complex as well as the stories surrounding it. Examples like The Crying Fist (2005), Fearless (2006), I Saw the Devil (2010) and A Bittersweet Life (2005) are not afraid to give emotional complexity to characters and their action scenes. I don’t want to come off as negative, because I do see small changes in western films like Warrior (2011) and Drive (2011) where we are starting to see some emotional complexity in the characters and how it leads into the fight scenes. It’s the independent film scene that will bring more depth to the action genre than a studio will because independents are less afraid to take chances.

Do you think Hollywood has made good use of Asian talent over the years?

Hollywood still needs to know how to use foreign talent effectively, especially when it comes to action. Like the final fight between Jackie Chan and Hiroyuki Sanada in Rush Hour 3 (2007) and when Jet Li fights Michelle Yeoh in The Mummy: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor (2008). The fights in both of these films should have been incredible with the talent they had, but it was a real let down.

The only film I feel that was a successful exploit of Asian talent was The Matrix because the Wachowskis were confident enough to let Yuen Woo-ping do what he needed to do with the training and the fight choreography.

I also feel action films are being replaced by the computer, meaning CGI. The problem with it is the audience knows the majority of the time it’s a computer generated drawing so their suspension of disbelief goes out the door. I’m not saying all CG is bad, but there needs to be a balance.

Who are your cinematic influences?

Bruce Lee was and still is a huge influence on me. He was such a ground-breaker and elevated the level of fight choreography to another level. When you look at his work on Game of Death (not the one released in 1978 but the Japanese Art Port version) you can see how he crafted his shots with his frame composition that worked artistically and had a cause and effect as well as a non-verbal narrative. He also brought a lot of grace and style to fight choreography that was not there before.

There’s also Jackie Chan. I have seen and studied every movie he’s made from 1976 to the present. He seemed to have no fear and always put his life on the line when it came to his films. There were so many imitators after Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow (1978) which meant he was always upping his game. He took the art of using the environment as a part of the fight to another level and added extreme stunts to the action, eventually separating himself from the rest of the pack.

I feel Sammo Hung is one of the most underrated action filmmakers out there. Some of Jackie’s best fights were under the direction of Sammo. Also, I was fortunate to have worked with the Yuen Clan and various members of their stunt team on different projects. I have learned a heck of a lot from them. They have always changed with the times and with technology.

Tong Gaai is someone who has not received his due for all the work he has done. His work on Vengeance (1970), The Avenging Eagle (1978), Killer Clans (1976), The Sentimental Swordsman (1977), and The Super Inframan (1975) is as complex and intricate as any of the works of the Yuen Clan. Also Bob Simmons. He was one of the stunt coordinators for Sean Connery’s James Bond films. The fights were very gritty, held a constant tension and told a story. I feel the Cold War Bond films starring Sean Connery and George Lazenby helped to shape and develop the set pieces in action films as we know them today.

Have you ever referenced their work?

When I first started stunt coordinating, I worked on a Roger Corman film called Hard as Nails (2001). One night the director, Brian Katkin, asked me to put together a fight scene at the last minute and I had only 15 minutes to choreograph the two-on-one fight. We had shot two action scenes earlier, it was really late (about 4am) and everyone was really tired because we had been there since 6am the day before. So, I woke up the stunt fighters that were in the scene and I told them what we needed to do.

The first thing that came to my mind was the final fight scene with John Liu, Wong Tao and Hwang Jang-lee in The Secret Rivals (1976). I loved that movie. I must’ve seen that movie at least 20-30 times in the theater growing up. So I used the final fight as a temporary template and created from there. I took the emotional, rhythmical and visual essence of what they did and changed it for the situation and time restraints. I used my own techniques and made it mine. We only had 20 minutes to film it, which meant we had only two takes to get it right. Because of the pressure involved, I felt this experience was something that definitely separated the men and the boys. It’s also called, “pulling a fight scene out of my butt!”

What fight scenes stand out – in your opinion – as great examples of the genre?

The brawl in the mall at the end of Police Story (1985) was incredible. The domestic fight scene between Temuera Morrison and Rena Owen in Once Were Warriors (1994) was so emotionally real that my knees were still shaking after I left the theater. The cat fight between the two gypsies and the brawl with Sean Connery and Robert Shaw in the train at the end of From Russia with Love (1963) was well shot and choreographed. Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow was a prime example of how fights that are integrated with the story can create a timeless classic. The follow up Drunken Master (1978) was much more complex with their choreography, but Snake has a stronger emotional resonance with the fights and the story.

The end fight between Lee Marvin and Ernest Borgnine on a moving train in Emperor of the North (1973) was a classic for the day. The late Benny Dobbins was the stunt coordinator as well as Borgnine’s stunt double and he takes the hideous blind tumble off the train the end. The trapping hands gun fight at the end of Equilibrium (2002) was something very clever and ingenious. The fight between Sammo Hung and Lau Kar-leung in Pedicab Driver (1989) is a classic. Also, the fight between Chen (Bruce Lee) and Petrov (Robert Baker) in Fist of Fury (1972). If you technically break down the fight, it’s fairly simple compared to the action we see today. But it still holds a raw emotional charge throughout the fight that many others have tried to replicate but simply cannot.

As a fight choreographer, is it better for you to work with actors who have no genuine martial arts experience?

How many black belts you have does not equate to instant success as a stunt fighter or an action star. A martial arts school teaches you how to defend yourself, build your confidence and self-esteem, prepares you for sporting competitions and/or is simply a place for physical recreation. It is not an acting school or a stunt school.

There was a myth that got people (including those in the entertainment industry) thinking that any martial artist could get into film without any type of a learning curve. It certainly is not true. If you look into the history of martial arts films in the west, you will see many high profile and world champion martial artists who were given the chance to star in a movie and failed. Only a handful were able to successfully make the transition. I see it all the time when a martial artist gets hired to fight on film. They have no acting or stunt training and they usually have a traumatic experience because they are not prepared and are pulled in all directions on what to do.

The solution is to have proper stunt training under an experienced stunt/fight coordinator, and take acting lessons. It will change your view and approach to the creative process. Display the same dedication to being an actor and filmmaker as you do with the martial arts. Trust me, you will thank me later.

For more information on John Kreng’s fight seminars, visit johnkreng.blogspot.co.uk, or follow on Twitter @jkreng.